Newsroom

Antibody in breast milk can be protective against asthma thanks to gut microbiota effects

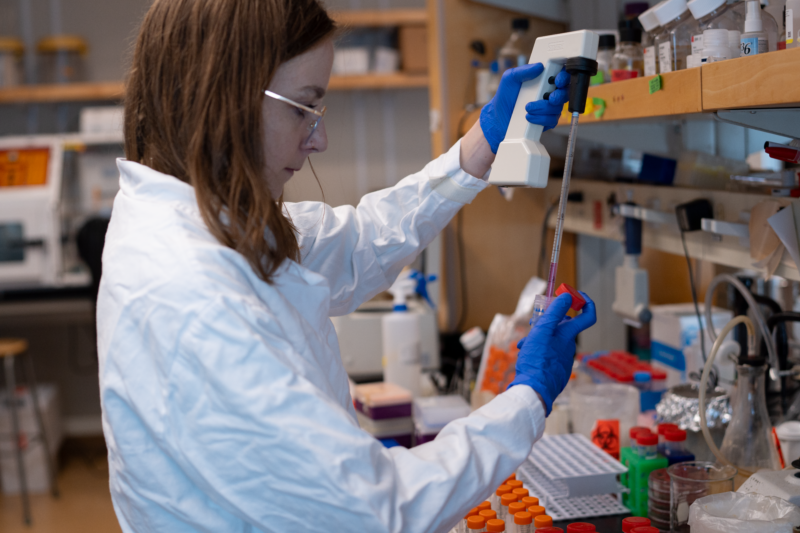

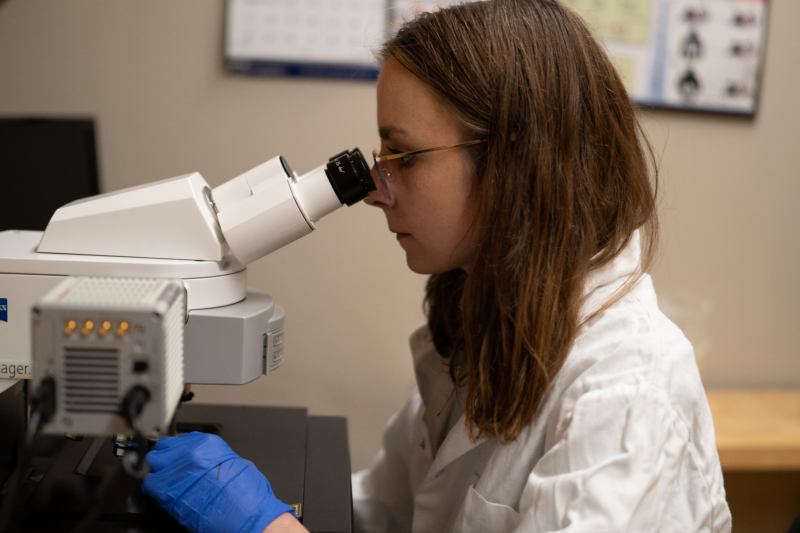

PhD candidate Kate Donald

A new study from the lab of Dr. Brett Finlay (Michael Smith Laboratories, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology) has demonstrated how breast milk might protect against the development of asthma in infants, by acting on the microbiome.

Published in Cell Reports, this work was led by PhD candidate Kate Donald.

“It’s known that breastfeeding is protective against many different diseases for infants, but we don’t know all the mechanisms behind this and there are a lot of different components of breast milk that can contribute,” shares Donald.

One key component of breast milk is IgA, an antibody that helps to eliminate disease-causing microbes in the gut. Since infants are born with an immature immune system and cannot produce IgA themselves, breast milk serves as their primary source of this protective antibody early in life.

Donald was particularly interested in studying the health effects of breast milk IgA in the infant microbiome. In this study, she used mouse models of IgA deficiency and asthma to see what relationships might exist.

She found that mice that received breast milk lacking IgA ended up having more of a bacterium in the gut known as segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). This bacterium, while not directly disease-causing, is known to be inflammatory and to stimulate the immune system.

She found that mice that received breast milk lacking IgA ended up having more of a bacterium in the gut known as segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). This bacterium, while not directly disease-causing, is known to be inflammatory and to stimulate the immune system.

This stimulation was observed in Donald’s study, as the SFB led to an increase in activity of Th17 cells, a type of immune cell that maintains health but also contributes to diseases such as allergies. With this increased immune system activation, there was a much more inflammatory response when the mice were exposed to the house dust mite model of allergic asthma.

This stimulation was observed in Donald’s study, as the SFB led to an increase in activity of Th17 cells, a type of immune cell that maintains health but also contributes to diseases such as allergies. With this increased immune system activation, there was a much more inflammatory response when the mice were exposed to the house dust mite model of allergic asthma.

So, without IgA coming in through breastfeeding, there were alterations in the gut microbiota which led to a more extreme allergic reaction. Mice were protected against this response if they received breast milk IgA.

As Donald summarizes, “IgA is protective against later development of a mouse model of allergic asthma by specifically targeting certain bacteria in the intestine and getting rid of them. Without breast milk IgA, these bacteria overstimulate the neonatal immune system.”

While Donald’s study was done using a mouse model, she has more recently been studying human milk samples to see if the same mechanism exists. The results so far have shown many parallels to her study in mice.

Donald explains the significance of this work, and how the knowledge of IgA’s importance should be applied outside the lab in the future.

“IgA is clearly an important component to consider. This study really supports making sure infants that can be breastfed, are, and for those that can’t, that the right alternatives are made for them to help promote healthy immune development.”